Review by Jonathan A. Wright

Creating Biophilic Buildings by Amanda Sturgeon FAIA

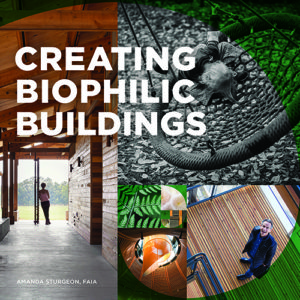

Amanda Sturgeon’s stunning new book, Creating Biophilic Buildings is, at first look, simply a pleasure to hold and to see in its nearly square and generous format and in the texture and illustration on the cover. The signature of this book lives in both its detailing and in her presentation of the path to a biophilic built environment. Sturgeon sets a personal and publishing standard, and, as Jason McLennan’s successor at the International Living Futures Institute, gives us an accessible and deep view into her thinking and mission.

Amanda Sturgeon’s stunning new book, Creating Biophilic Buildings is, at first look, simply a pleasure to hold and to see in its nearly square and generous format and in the texture and illustration on the cover. The signature of this book lives in both its detailing and in her presentation of the path to a biophilic built environment. Sturgeon sets a personal and publishing standard, and, as Jason McLennan’s successor at the International Living Futures Institute, gives us an accessible and deep view into her thinking and mission.

She demonstrates that biophilia is not just a bright light on the bird of paradise flower in an exquisite vase, but a grand-scale knitting-together of plant and soil and wood and sky in familiar, intimate, and at times arresting patterns. This book will carry you on that road.

As a builder connected to the development and construction of two Living Buildings, I am somewhat familiar with the concept of biophilia. But for us, the biophilic details were not specifically in focus during our planning and construction assignments—we were busy chasing procurement, systems, and trade talent. In spite of this, working in the presence of biophilic design was unmistakably inspirational. So for me, this book provides the structure to understand much more deeply what we experienced daily in the building work.

Sturgeon lays out the six core principles in Stephen Kellert’s defining work on biophilia and then uses those as the lens through which to examine and reveal the built projects selected for the case studies. These design elements and attributes are: environmental features; natural shapes and forms; natural patterns and processes; light and space; place-based relationships; evolved human-nature relationships. Each is accompanied by underlying characteristics. For example, “natural shapes and forms” includes “botanical motifs” and “tree and columnar supports.” The thinking is clearly presented and accessible.

The book is beautifully written, as it would need to be to carry and embody this profound message. In the introduction, Sturgeon comments: “Like any relationship, our bond with the natural world requires nurturing. If we do not attend to it, this relationship can wither and die, leading to indifference or even contempt. We are already seeing the disastrous consequences of this estrangement in habitat destruction, species extinction, and pollution.” The assignment to building makers, then, is to build exquisite bridges between human activity and natural systems.

Sturgeon further observes that attempts by project teams to incorporate biophilic design are often reduced to adding plants and water. She challenges teams: “Nothing in their training or backgrounds has prepared them for this (biophilic) exercise, and their experiences with green building rating systems has trained them to fulfill the minimum requirement of a checklist without thinking past that step. True biophilic design goes much further and deeper, drawing on the intrinsic psychology that is mapped in our brains calling for us to be deeply connected to the natural world.”

The book makes thoughtful, restful, yet stirring, reading. The chapter “Case Studies Through Time” sets the stage, with examples of biophilic building from Mesa Verde, Falling Water, The Sydney Opera House, and the Iroquois Longhouses. This armature helps me understand that biophilia is what and who we are and have been—it just has been tamped down by our design, development, and construction processes. In the fourteen case studies presented in Creating Biophilic Buildings, it becomes clear how biophilia can be revealed and celebrated in a huge variety of ways.

Probably the most arresting design in the case studies is the Vandusen Botanical Garden Visitors Center in Vancouver. The sweeping accessibly ofnatural forms carry a message of integration and majestyalong with an efficient, interactive welcome and environment for visitors. The smallest example in the case studies, the Bertschi School addition of 5200 square feet in Seattle, carries a huge inspirationand message to and about the young people who learn there. I visited the school with the team from Hampshire College on a cold, rainy, and dark December afternoon and enjoyed its cheery and engaging spaces and features. I liked the “runnel” that carried drainage water through a channel under the classroom floor, covered by a glass plate. The children do too—they can watch the water, be soothed by it, and be intrigued as well. Building elements that nourish and settle us and that also engage our curiosity—that’s magic, especially for those of us who build them. The plants in the water treatment garden are labeled with small ceramic QR codes. Bend down close to see the plants up close, and then click with your phone for more information.

Notably, Creating Biophilic Buildings includes successful, publicly-owned buildings and buildings of modest budget and deep commitment. It is key for all of us to note that nature-based sustainable design and construction is not for the boutique and trophy world. It is our common calling and destiny.

One can open this book almost anywhere—as if it were an anthology of short stories—and key in on something interesting. Or you can start at the beginning and get to work. I have done both, and both are deeply satisfying. When I travel, I go to interesting buildings and museums. Even more interesting is to visit the Living Buildings in new places because they are place-based and-purpose centered. Desert Rain in Bend, Oregon was captivating, and I am very excited to visit Te Kura Whare Cultural Center in Taneatua New Zealand in January 2018.

Our best buildings, with the help of their designers, builders, and occupants, tell our story in a unique way. Amanda Sturgeon shows us that biophilic buildings speak up, loud and clear, in a universal human and world language about their place and mission, in their own universally understandable dialect. Her book isin every way a call to kindness, a summons, and a commanding invitation to befriend and mend our hearts, and the earth’s heart too, through our best work.

**********************************************************************************

Our Mission

NESEA advances sustainability practices in the built environment by cultivating a cross-disciplinary community where practitioners are encouraged to share, collaborate and learn.

Hi Jonathan,

Stephen Keller was a very engaging professor at the Yale School of Forestry when I was there in 1987. This was before climate change was a significant threat and carbon was sequestration was a discussed. I have since used my forestry background to build a window weatherization company that seeks to weatherize existing window and repair as many existing windows as I can. Biological organism have the ability to repair themselves because it is less energy intensive that replicating oneself from scratch. I would love to see this as a founding princicple in how we move forward with regard to new and existing buildings. Thanks for your thoughtful post. Chris Pratt