Unfolding Community Resilience

"May we live in interesting times," goes the ancient Chinese saying, conveying both a blessing and a warning. In the face of extreme weather conditions—unusual and repetitive water, heat, and wind events—and severe depletions of natural resources, the landscape that NESEA practitioners face differs greatly from that of our predecessors. In these interesting times we think we know what to do—make tighter buildings— but in reality we must begin to address much larger issues in the resilience of the communities around our buildings.

"May we live in interesting times," goes the ancient Chinese saying, conveying both a blessing and a warning. In the face of extreme weather conditions—unusual and repetitive water, heat, and wind events—and severe depletions of natural resources, the landscape that NESEA practitioners face differs greatly from that of our predecessors. In these interesting times we think we know what to do—make tighter buildings— but in reality we must begin to address much larger issues in the resilience of the communities around our buildings.

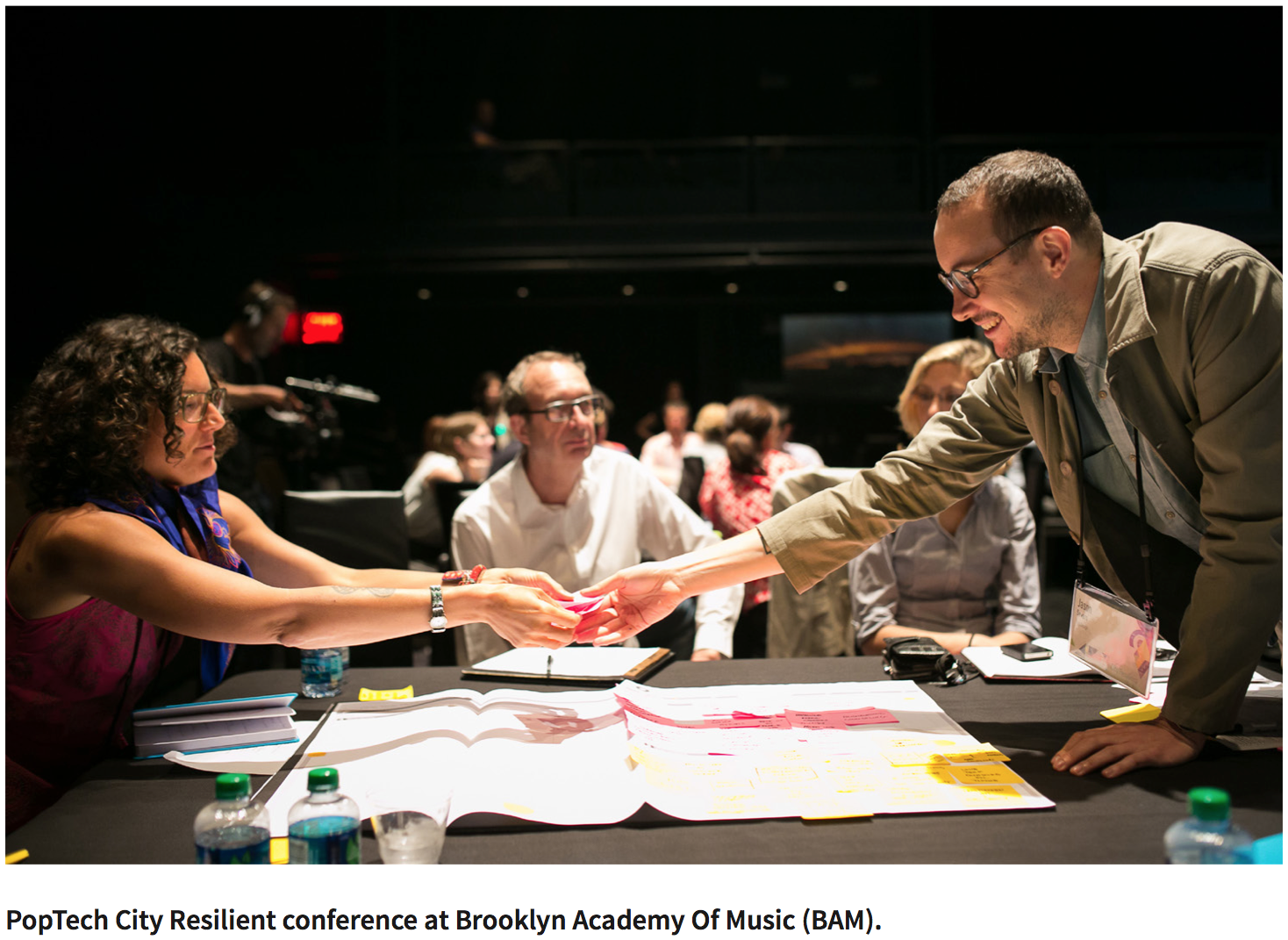

At the BuildingEnergy conferences in 2013 and 2014, I served as a co-chair for the Resilient Cities track. This article was inspired by those rich conversations, which made it clear that sustainability thinking and practice will not be enough to make our communities thrive.

We must move beyond sustainability and embrace resiliency.

Resiliency means not just rebuilding, but learning from disaster to create a better future. One disaster prepares a community for others. As the community leaders of Newtown, Connecticut said: "Without the experience of the previous hurricane and snow storm, the town would not have come through, with resilience, the shootings at the Sandy Hook elementary school." What the town learned from severe weather, it was able to apply to an entirely different sort of tragedy. It was, in a word, resilient.

Unfolding

Making energy-efficient buildings—even net-zero energy ones—will not maintain our communities in the face of a radically different adverse conditions. Going forward, we must think and practice beyond the building by using whole-systems thinking to build resilient communities.

"Unfolding," a core idea of architect Christopher Alexander's thinking, will serve as a useful guide to this discussion.(1)

Unfolding occurs when one walks the land to discern what the land wants built. This process meanders and is nonlinear. It takes time. We can see ourselves as being in the same unfolding process with the shift from sustainability to resilience. We must observe and sit with the earth and the concept of resilience so we can determine what to do next.

Sustainability has served as the NESEA mantra for many decades. I believe it is time to envision a new, more holistic mission. Sustainability is about limiting adverse impacts of people on the the planet through reduction of our natural resource use. By contrast, as C.S. Hollings said, "Resilience is a way of conceptualizing the ability to change and adapt. The best resilient systems don't just bend and snap back. They get stronger because of stress. They learn." (2)

We think most often about resilience in terms of our response to natural disasters. Andrew Zolli (3) describes resilience as the product of the response of various professions. For the emergency responder, the focus is getting people safe and critical systems back up. The psychologist helps people deal with trauma. Businesses install redundant systems so the doors stay open for customers. Although their specific responses differ, these three professions—emergency responder, psychologist, and business person—employ a common approach. They adapt, aim to foster continuity, and learn from adversity. Resilience does not mean a community returns to its original state. Both people and systems must anticipate what to change so the community might better withstand future shocks.

We think most often about resilience in terms of our response to natural disasters. Andrew Zolli (3) describes resilience as the product of the response of various professions. For the emergency responder, the focus is getting people safe and critical systems back up. The psychologist helps people deal with trauma. Businesses install redundant systems so the doors stay open for customers. Although their specific responses differ, these three professions—emergency responder, psychologist, and business person—employ a common approach. They adapt, aim to foster continuity, and learn from adversity. Resilience does not mean a community returns to its original state. Both people and systems must anticipate what to change so the community might better withstand future shocks.

Four Moves Toward Resilience

We can explore our move toward resilience in four areas: community, buildings, infrastructure, and the "soul of the world." Already part of our practice, the areas of buildings and infrastructure will come easily to NESEA members. Fostering community and soul, although harder goals to grasp, are vital for improving the human condition. These two areas are discussed in depth below, as they are the least familiar to most of us and arguably the most important to understand.

Resilient Communities

Research demonstrates(4) that communities with tighter ties among people— regardless of age, sex, race, or class— survive threats of extreme weather, heat, or flooding better than those with loose ties.

We must create people and neighborhoods that can survive and even thrive after a disaster. Yes, the buildings must be resilient, but so must the people living in and around them. As designers, we must keep asking: where are the areas of public community refuge?

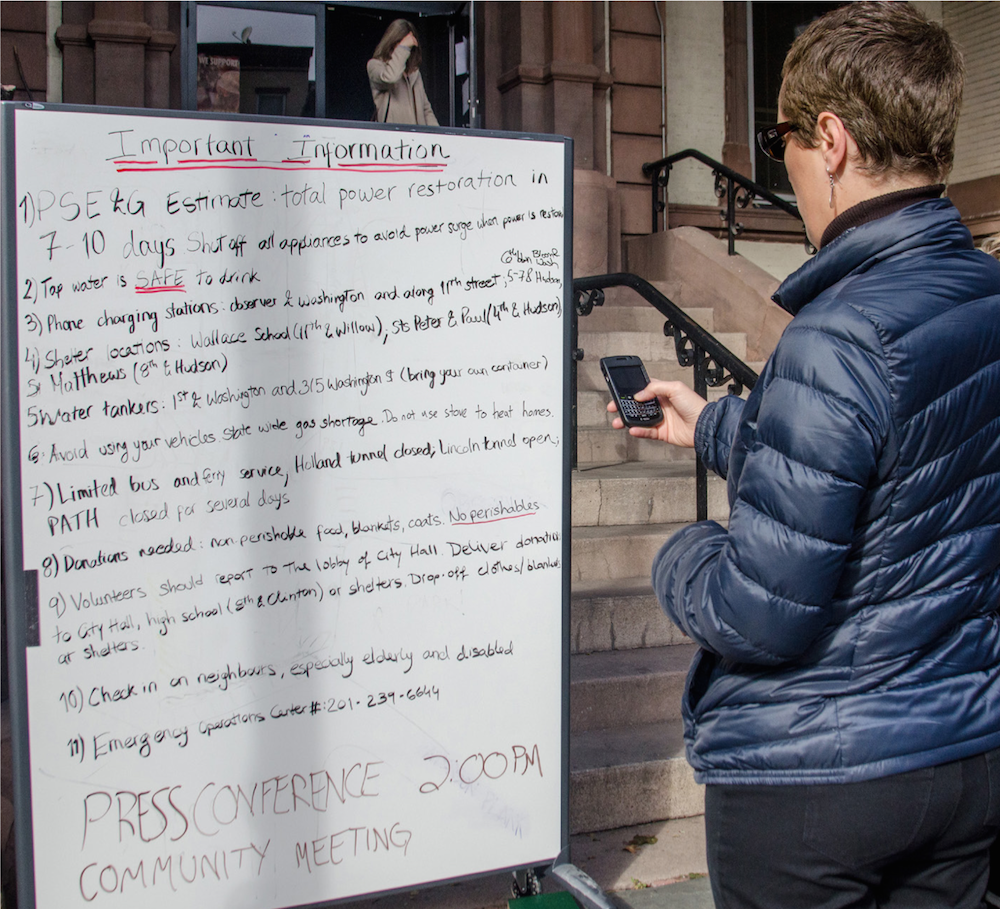

Developing community resilience requires a network of local businesses that agree to stay open when disaster hits to provide for basic needs like food. We must develop an information infrastructure to disseminate this information. Think about your neighborhood. In the face of a disaster, does the social fabric come together or tear apart? What is the community connectivity rating or altruism index? (This can be measured by the presence of community gathering places such as farmers markets, spiritual places, and bars.) The presence of known community resources tempers hostile resource wars in the face of scarcity. Neighborhoods need known public places of community refuge that have the basic resources for survival, places where people know they can go in a disaster. Distribute lists of mobile phone numbers of people in your neighborhood. What is the walking score to reach the basic amenities of your place? If there is no gas for your car or transportation, where are the amenities you need that you can walk to?

After a disaster, members of a community are the brains for directing and organizing recovery and learning. The recovery effort has to be collaborative and consensus-based or we all suffer. Communities can identify the natural neighborhood conveners and organize them in advance. Build community resilience peer-to-peer, one person at a time. In Connecticut, for example, volunteer Community Emergency Response Teams go house to house after a disaster to check on people's well-being. Their work supports first responders and frees them for work requiring higher levels of training. In Boston, the Jamaica Plain New Economy Transition holds an emergency preparedness pie-eating party to inform community members about available resources.

Resilient Buildings

We face a central question when it comes to the resiliency of our building stock: rebuild on or retreat from land hit by a natural disaster? Going forward, we must learn from building performance in natural disasters, then use that intelligence to determine where to build. We should not automatically rebuild what was there before, because the risks of the past are not the risks of the future. Instead of rebuilding, we ought to analyze the conditions to establish criteria for retreating or rebuilding.

Resilient Infrastructure and Systems

Resilient Infrastructure and Systems

A resilient community must have flexible infrastructure, both for information and services. Smart phones, for example, can be used in emergency communication mode by disabling data downloads and camera use. This emergency approach maximizes the life of the phone and pro- vides access over a longer period of time.

When designing, we can think about what utilities and resources are underground, and try to get them moved above ground. In an emergency situation with limited fuel and electricity, getting to underground utilities becomes very difficult. We should consider all hazards such as wind, heat, and flooding in both buildings and communities. How does a building operate? How does its landscaping interact with the forces of nature? We should look at the vulnerability of assets in the face of multiple hazards.

Resilient Soul of the World

Soul is a slippery notion. It is murky, squishy, and even, at times, dark. One might say soul is what is underneath our culture: the underground, muddy, the underbelly. But soul holds up the culture; it keeps us unfolding in community. With soul comes intimacy and reflection.

Our experience of soul might occur as we walk on the street and stop in our tracks, arrested by the face of an elder or the patina of an old building. Soul does its work when it slows us down to experience another face or look at a parking meter. It is the continuous layering of memories, of our collective stories as well as our tales of rogues and community leaders. Memories are honored in what was built at different times, for different purposes, and with different architectural styles. A building does not have to be classical or traditional to reveal soul. Soul is what is unknown, either longing to be revealed or to remain unknown, or what is unfinished, what is to come next in a place.

To experience soul, we must let go of our rational minds and drop into it. We can't fully know the soul of a place through our head. To glimpse the richness of soul in a place, we must feel it. The soulful way is slowly attending to the particulars of a place: —that lamp post, this curb, that storefront—all arresting us in profound imagination.

The door into soul is not the mind, but aesthetics. Here we are, at the root of aesthetics, breathing in through our senses, noting an arresting image or experiencing the presence of another person on the street. The heart is opened, the body tingles—that is the aesthetic response. Beauty is present.

Soul reveals beauty, which is what must be present in a neighborhood for us to bond with the place and each other. Resilience requires these tight bonds. And without a deep sense of soul, community resilience is a fleeting potential.

Coda

As practitioners and thinkers we have much to learn about resilience of communities, buildings, the infrastructure, and the soul of the world. It will be a whole system in action. We are in for bigger and bigger shocks. Right now we need less science and a bit more art until the science beyond building science is better known. And even as we evolve the science, art and aesthetics must be present shaping our places.

3. Andrew Zolli and Ann Marie Healy. Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back. Free Press. 2012.

Learn more about Resilient Cities & the BuildingEnergy 15 Conference & Trade Show: http://nesea.org/be15

Our Mission

NESEA advances sustainability practices in the built environment by cultivating a cross-disciplinary community where practitioners are encouraged to share, collaborate and learn.

Add comment